During World War II, Germany developed some of the earliest precision‑guided weapons. Among them was the Ruhrstahl SD‑1400 X—better known as Fritz X or FX 1400—a radio‑guided glide bomb designed to punch through battleship armor. Weighing roughly 1,570 kg and carrying a 320‑kg armour‑piercing warhead, Fritz X was based on the unguided PC 1400 but added cruciform wings and a special tail with radio‑controlled spoilers This design allowed the bomb to dive at transonic speeds (up to 1,235 km/h) and penetrate nearly 20 cm of armour plating, making it ideal for attacking heavy warships.

Design and Guidance

The bomb’s guidance system was developed by Max Kramer at the Luftwaffe’s Berlin‑Adlershof research establishment. It used the Kehl‑Straßburg FuG 203/230 radio‑command link, which allowed the bombardier to steer the bomb with a joystick (Manual Command to Line‑of‑Sight). Five colored lights in the bomb’s tail indicated direction changes to the operator. Because the operator had to keep the bomb and target in view, launching aircraft had to fly high and straight—often at altitudes around 20,000 ft—which made them vulnerable to fighters and anti‑aircraft fire. Trials at Peenemünde showed that 50 % of Fritz X bombs landed within roughly 14 m of the aim point, a remarkable accuracy for the era.

Launch Platforms

The Luftwaffe equipped only a handful of aircraft to carry Fritz X. Dornier Do 217K‑2 bombers of III./KG 100 were the primary launchers; these aircraft were fitted with Kehl transmitters and wing racks for the heavy bomb. Later K‑3 and M‑11 variants also carried Fritz X. The bomb was initially tested on Heinkel He 111s but never used in combat from that platform. A few Heinkel He 177A‑5/R1 long‑range bombers were modified with Kehl control gear and could carry multiple Fritz X or Hs 293 weapons, but operational use appears to have been limited. A technical analysis conducted after the war noted that most recorded Fritz X deliveries were by Do 217K‑3 or He 177 aircraft of KG 40 and KG 100.

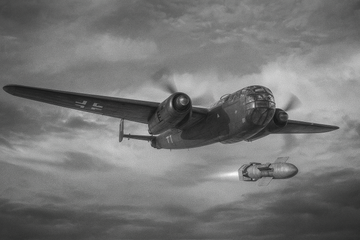

( An early version of the Fritz X was tested from a German Heinkel He 111 bomber, where the operator directed the bomb toward its target from within the aircraft )

( An early version of the Fritz X was tested from a German Heinkel He 111 bomber, where the operator directed the bomb toward its target from within the aircraft )

First Operational Deployments

Fritz X first saw combat on 21 July 1943, when Do 217s of KG 100 attacked Allied shipping in Augusta harbour, Sicily. Allied records do not indicate any hits, and the true nature of the weapon remained unknown. Later that summer, II./KG 100 tested the bombs against Royal Navy ships in the Bay of Biscay; a near miss on the sloop HMS Landguard was recorded on 25 August, and a second attack on 27 August sank the sloop HMS Egret and badly damaged the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan. These attacks used a mix of Fritz X and Hs 293 glide bombs and led the Royal Navy to withdraw surface ships from the Bay until the guided‑weapon units moved to the Mediterranean.

Striking the Italian Fleet

The weapon’s most famous success came after Italy signed an armistice with the Allies. On 9 September 1943, a 17‑ship Italian fleet—including the battleships Roma, Italia and Vittorio Veneto—sailed for Allied ports. Do 217s from III./KG 100 shadowed the ships near Corsica and attacked with Fritz X bombs. According to the National Air and Space Museum, the bombs scored two direct hits on Roma, penetrating the deck and exploding deep in the ship; secondary explosions in the magazines caused the battleship to capsize and sink, killing more than 1,300 sailors. Italia (formerly Littorio) was also hit but reached Tunisia after temporary repairs.

Operation Avalanche and the Salerno Landings

When Allied troops landed at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), the Luftwaffe’s guided‑weapon units switched targets. On 11 September 1943, a Fritz X pierced the roof of the American light cruiser USS Savannah’s “C” turret and detonated in a lower ammunition room, killing 197 sailors and knocking the ship out of action for eight months. The same morning, a bomb narrowly missed USS Philadelphia. Two days later, on 13 September, a Fritz X passed through seven decks of the British light cruiser HMS Uganda and exploded beneath her keel, extinguishing boiler fires and causing extensive flooding that required her to be towed to Malta for repairs.

German bombers continued to harass the invasion fleet. A history of the Salerno campaign notes that on 14 September a guided bomb (possibly Fritz X or Hs 293) sank the tanker Bushrod Washington, and on the 15th another bomb wrecked the cargo ship James W. Marshall, later used only as part of an artificial harbour. The assault reached its climax on 16 September when the battleship HMS Warspite—providing gunfire support—was struck by three Fritz X bombs. One round penetrated six decks into the No. 4 boiler room and blew a hole in the hull, flooding the ship and knocking out all power; nine sailors were killed, and Warspite had to be towed for repairs. She was out of action until the Normandy landings in June 1944 but later returned to bombard German positions during Operation Overlord. A final attack on 17 September produced near misses on USS Philadelphia and damaged the Dutch sloop HNLMS Flores and British destroyer HMS Loyal.

Later Operations

Fritz X saw intermittent use after Salerno. The Australian Defence analysis notes that the light cruiser USS Philadelphia and British cruiser HMS Spartan were among other casualties. The bomb was reportedly used against the HMS Spartan off Anzio on 29 January 1944, sinking the ship with heavy loss of life. German records also suggest that KG 100 attempted to attack a bridge over the Sélune River at Pontaubault on 7 August 1944 to slow the U.S. 6th Armored Division. Toward the end of the war, a few Fritz X bombs may have been launched at bridges on the Oder River.

Countermeasures and Legacy

The sudden appearance of guided bombs shocked Allied navies, but countermeasures quickly reduced their effectiveness. The British Type 650 radio jammer and other devices interfered with the Kehl‑Straßburg command link. Allied air superiority forced Luftwaffe bombers to higher altitudes, while evasive manoeuvres, smoke screens and heavy anti‑aircraft fire further degraded accuracy. German engineers responded by developing wire‑guided versions and employing Henschel Hs 293 rockets for lightly armored ships, but by 1944 the guided‑bomb threat had diminished. Of roughly 1,400 Fritz X bombs produced, about half were expended in trials and training.

Although Fritz X did not change the outcome of the war, it pioneered a new era of precision‑guided munitions. Its successes against Roma, Savannah and Warspite demonstrated the vulnerability of heavy ships to high‑altitude stand‑off weapons. The design influenced post‑war development of air‑to‑ground missiles and cruise weapons. For aviation historians, the story of Fritz X—alongside the Dornier Do 217 and other launch aircraft—illustrates how rapid innovation can momentarily tip the scales of naval warfare, even as countermeasures and tactics evolve to counteract new threats.